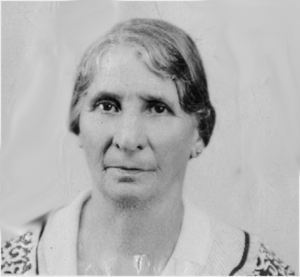

Nonna. The Italian word for grandmother. Pictured to the left is my mother’s nonna (and my “bisnonna” – great grandmother), Domenica Scaccia. The photo was taken in Sicily sometime after her marriage in 1893 and before she emigrated to America in 1912. When I compare this photo with her wedding portrait, I see the face of someone older than the teenager she was at the time of her marriage. I see a face devoid of even the hint of a smile and with eyes that seem to express a steely resolve with just a touch of sadness. I also noticed her prominently displayed left hand which, curiously, had a ring on her little finger rather than on her ring finger. After researching the possible symbolism behind this, I’m fairly certain that it signifies a change in her marital status. There are numerous websites that discuss the meaning of rings worn on different fingers and the consensus seems to be that someone wearing a ring on the little finger is divorced, single, or has made up her mind to remain single. Her husband, Vincenzo Spera (my “bisnonno”), died in Buffalo, New York in 1902 (just three and half months after coming to America). Since Domenica is no longer dressed in black, which would indicate that at least a year had passed since Vincenzo’s death, I believe it’s safe to assume that this portrait was taken after 1903 when she was between the ages of twenty-nine and thirty-eight and her emigration from Sicily was in her very near future.

Nonna. The Italian word for grandmother. Pictured to the left is my mother’s nonna (and my “bisnonna” – great grandmother), Domenica Scaccia. The photo was taken in Sicily sometime after her marriage in 1893 and before she emigrated to America in 1912. When I compare this photo with her wedding portrait, I see the face of someone older than the teenager she was at the time of her marriage. I see a face devoid of even the hint of a smile and with eyes that seem to express a steely resolve with just a touch of sadness. I also noticed her prominently displayed left hand which, curiously, had a ring on her little finger rather than on her ring finger. After researching the possible symbolism behind this, I’m fairly certain that it signifies a change in her marital status. There are numerous websites that discuss the meaning of rings worn on different fingers and the consensus seems to be that someone wearing a ring on the little finger is divorced, single, or has made up her mind to remain single. Her husband, Vincenzo Spera (my “bisnonno”), died in Buffalo, New York in 1902 (just three and half months after coming to America). Since Domenica is no longer dressed in black, which would indicate that at least a year had passed since Vincenzo’s death, I believe it’s safe to assume that this portrait was taken after 1903 when she was between the ages of twenty-nine and thirty-eight and her emigration from Sicily was in her very near future.

Except for a dimly remembered trip to Brooklyn in the early fifties to visit her, Domenica was absent from my life, so I had to rely on my mother’s recollections of her and, after mom died, those of her sister, Ann Cavaliero. Nonna was, by all accounts, the archetypal Italian grandmother – loving, caring, protective, and tough as nails.

When I accessed the municipal records of Vallelunga Pratameno, Sicily, I was able to find Domenica’s birth registration which was dated January 2, 1874. Her parents were Andrea Scaccia, age 38, and Antonina Amenta, also age 38. Interestingly, the two municipal officials who signed her birth certificate were Pietro Parisi and Pasquale Sinatra. I then searched for Andrea Scaccia in the death index and found him in 1897. His “Atti di Morte” (death registration) listed his age at 67 and his place of birth as Montemaggiore. His parents were Santo Scaccia and Domenica Catalano. Finally, he was listed as the “sposo” (groom, spouse) of Antonina Amenta. All the information on this record confirmed everything that my grandfather had told me about his mother’s parents.

A search for Antonina Amenta yielded nothing. I did find two death records for that name, both with the same parents, Antonino Amenta and Calogera Cardinale. The first one in 1890 was for an infant, age thirteen months. The second was dated 1892 for another infant who only survived one hour. No ages are given for Antonino or Calogera, so any relationship to my Antonina Amenta would be sheer conjecture. Given the recurrence of names in these family trees as well as the naming traditions of the time, I would imagine that this seemingly related branch of the Amenta family could descend from a cousin of my great, great grandmother.

In any event, this is where the trail to Nonna’s maternal ancestry ran cold. Records for other towns in Caltanisetta were also available. Montemaggiore Belsito, however, was not one of those towns. I had resigned myself to the fact that I would either have to go to Sicily to research my Scaccia and Amenta lineages, or I would need to resort to the lengthy, time consuming snail mail letters of inquiry to the Montemaggiore municipal offices. Then, in early 2012, I had the great, good fortune to encounter online a researcher, Donna Arcara, who was also searching Sicilian records and was having difficulty translating the microfilmed records that she had ordered from the LDS repository. As I mentioned in one of my initial posts (“Bloodlines, Breakthroughs & Brick Walls, Part 1”) that the LDS church, a.k.a. the Mormons, have assembled the largest collection of genealogical data in the world and it was from these archives that Donna had retrieved records on her husband Greg’s family. I am a firm believer in the practice of “random acts of genealogical kindness” so I contacted Donna and volunteered to help her decipher her acquisitions.I very quickly learned through our correspondence that Donna was focusing her search for Greg’s ancestors in Montemaggiore Belsito! Donna, like so many other family historians, is an enthusiastic and generous soul and she offered to be on the lookout for any Scaccias in her examination of the Montemaggiore records.

Shortly after making that offer, she emailed me four birth records, the most important being that of my great, great grandfather, Andrea Scaccia. In addition to confirming the information gleaned from Andrea’s death record, i.e. the names of his parents, I also learned their ages at the time of Andrea’s birth. Santo was fifty-two, making his birth year circa 1789. Domenica Catalano was twenty-eight, making her birth year circa 1803. In addition to Andrea’s birth record, Donna had also found and sent the birth records of three of Andrea’s siblings, Domenico, Rosaria, and Nicosia.

The marvelously serendipitous encounter with Donna Arcara led to each of us learning valuable information about our targeted ancestors and had the added, unexpected bonus of establishing a friendship with a kindred spirit. In my search for family history, I have made new friends, re-established old friendships, discovered new cousins, contacted distant relatives, and renewed dormant relationships. It has been a richly rewarding journey so far, a journey made more joyful by all the delightful people I have met along the way.

I will leave the reader with two more photos. The first is of Nonna,  Domenica Scaccia, and was taken in 1944 for her citizenship papers. The other is Domenica’s mother, Antonina Amenta, date unknown.

Domenica Scaccia, and was taken in 1944 for her citizenship papers. The other is Domenica’s mother, Antonina Amenta, date unknown.